Chiswick Timeline of Writers & Books: A quick guide

From the Writers Trail:

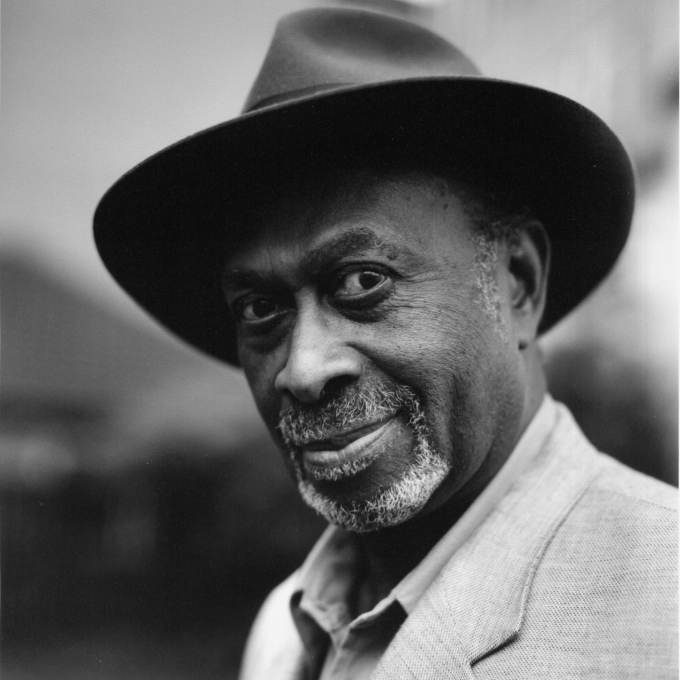

AA) James Berry OBE 1924-2017. Windrush poet. Seven collections, including Windrush Songs (2007) and A Story I Am In: Selected Poems (2011) from Bloodaxe. Plus books of poetry and short stories for children, winning the Smarties Prize (1987), the Signal Poetry Award (1989) and a Cholmondeley Award (1991).

Homecross House, Fishers Lane, W4 (Private residential home, no access).

James Berry 1924-2017 The Poetry Society

James Berry (poet) Wikipedia

Windrush Poet James Berry has died ChiswickW4.com

The Poet James Berry Black History Month

British Library acquires the archive of James Berry

1. James Berry in Chiswick

For 20 years, James Berry spent weekends in Chiswick with his partner Myra Barrs, who lived in Queen Anne’s Gardens. He moved into a flat of his own in Homecross House, Fishers Lane, in 2003, where he was filmed giving a reading: Windrush Songs – James Berry filmed at home in Chiswick. He lived there till 2011, when Alzheimer’s Disease led him to go into a nursing home and he died in 2017. His books continue to sell well. In 2020, a picturebook ‘A Story about Afya’ was published, and in August 2022 his poetry book for children, ‘Only One of Me’, is being reissued. His literary archive was acquired by the British Library and is being catalogued: it is due to be opened to the public this summer. The James Berry Poetry Prize for emerging poets of colour was set up in his honour in 2021.

Myra Barrs says: “James shuttled between Brighton and Bedford Park for 20 years before eventually coming to live in Homecross House. He had so many books and papers that he needed his own space. When he went into care in 2011 his archive was bought by the British Library. He did enjoy living in Chiswick very much and we walked a lot, by the river, in Kew, and with daily walks (between our two houses) across the common.”

2. From his publisher Bloodaxe Books

The Jamaican-born poet James Berry has died, aged 92. He had been suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease for several years, and died from a heart attack at a nursing home in London on Tuesday 20 June 2017.

James Berry grew up in a tiny seaside village in Jamaica. He learnt to read before he was four years old, mostly from the Bible, which he often read aloud to his mother’s friends, and was writing poems and stories from an early age. When he was 17, he went to work in America, but hated the way black people were treated there, and returned to Jamaica after four years. He came to Britain in the first wave of postwar wave of Jamaican emigration, sailing on the SS Orbita, the second ship after the Windrush, and sharing many of the experiences that prompted this migration in search of change and a better life. His poems explore the different reasons his fellow travellers had for leaving the Caribbean when they rushed to get on the boat. They also look back on slavery and individual experiences of hardship and trying to make a living: ‘Mi one milkin cow just die! / Gone, gone – and leave me / Like hurricane disaster!’

In London he attended night school and worked as a telegrapher while also writing, but it wasn’t until three decades later, in the mid-1970s, when he was in his 50s, that he became a published poet. One of the first black writers in Britain to achieve wider recognition, he rose to prominence in 1981 when he won the National Poetry Competition, the first and only non-white poet to win this prestigious prize.

Poetry mattered to Berry from an early age, exposed to two main languages: the standard English of Bible and prayerbook heard every Sunday at church, with all its rhythms and sounding patterns; and the tunes of everyday Jamaican language, with its sayings and proverbs, its special dialect words with their African connections, its expression of a roots culture. These experiences gave him that strong and particular Caribbean awareness of language which nourished his poetry – written in both idioms – over many years.

Much of his poetry celebrates the divided world of a lifelong outsider. Growing up in Jamaica, Berry felt as much disturbed by his African background as by the European slave-trade and its aftermath. His poetry shows how ‘root agonies’ made him view Africa as a thoughtless and neglectful mother, how his years in Britain – most of his adult life – left him worried by past, present and future. Yet despite these powerful feelings of hurt, of anger at injustice, Berry’s poetry is powerfully lyrical and full of delight in nature, and human nature. He vividly recalls the sounds and sights of his childhood, and in his work there is always a nostalgia for clear water and sunshine and ripe fruit. He himself observed that West Indian poetry ‘has something to say and there is a compulsive beauty about the way it is being said’. It is this compulsive beauty that Berry’s poetry communicates so strongly.

His numerous books include two seminal anthologies of Caribbean poetry, Bluefoot Traveller (1976) and News for Babylon (Chatto, 1984), and seven collections of poetry, including Fractured Circles (1979) and Lucy’s Letters and Loving (1982) from New Beacon Books, Chain of Days (Oxford University Press, 1985), and Hot Earth Cold Earth (1995), Windrush Songs (2007) and A Story I Am In: Selected Poems (2011) from Bloodaxe Books. He also published several books of poetry and short stories for children (from Hamish Hamilton, Macmillan, Puffin and Walker Books), and won many literary prizes, including the Smarties Prize (1987), the Signal Poetry Award (1989) and a Cholmondeley Award (1991). He was awarded the OBE in 1990.

3. Poet Hannah Lowe, who presented a Radio 4 feature on James Berry in 1995, writes:

‘James Berry was a pioneering writer, educator, editor and activist – a wonderful poet whose writing for both adults and children was characterised by compassion, humour and an acute eye for the political and social factors that shaped his life, and the lives of others. At 92, he was one of the last surviving literary voices of the early Windrush Generation.’